Team SIK is organizing a CTF based hacking event, to participate in which every hacker needs to reverse engineer four android apps (well, at least one of them) of varying difficulty levels, ranging from trivial to hard. Each app includes a secret password hidden inside, which is to be found in order to complete that level. The apps are available at https://goo.gl/vMj6b6.

This post discusses some of the ways that one could go about reverse engineering these apps in order to find the hidden password. I used dex2jar, apktool and JD-GUI and jdb for decompiling and analysing the apps, and Genymotion as the emulator. But, any other tools for these purposes should work as well.

Trivial

Solving the trivial challenge is as simple as running the app in Genymotion and entering an incorrect password. Run logcat to watch the logs as you enter a password. The app prints out the password in the logs when verifying the password.

D/dalvikvm( 393): GC_CONCURRENT freed 1169K, 25% free 7591K/10064K, paused 0ms+2ms, total 11ms

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 393): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)

D/Top Secret( 1417): Checking if input is equal to sik2016

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 393): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)

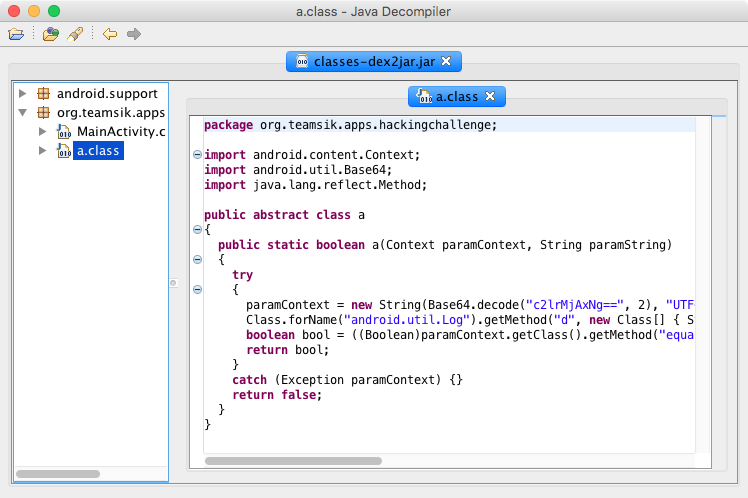

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 393): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)Another way to find the password is to unzip the APK file, use dex2jar to convert classes.dex to jar file, and studying the code for class a. The password can be found hardcoded in the code in base64 encoded form.

This can be decoded on the command line using base64 command line tool.

$ base64 -D <<< c2lrMjAxNg==

sik2016Easy

The second app takes a bit more effort than the first one to reverse engineer. The classes.dex file can be converted to jar file and opened in JD-GUI for easier analysis. The app verifies the password by first running the user input through an encryption algorithm. The algorithm works by first swapping out the two nibbles of every byte and then XORing the result with 0x42. It then matches this encrypted value to an encrypted value that is hardcoded in the app in base64 encoded form (BFF1NwF1YRTl).

Here is the encryption algorithm.

private static byte[] a(String paramString)

{

paramString = paramString.getBytes();

int i = 0;

while (i < paramString.length)

{

paramString[i] = ((byte)(paramString[i] << 4 & 0xFF | paramString[i] >> 4));

paramString[i] = ((byte)(paramString[i] ^ 0x42));

i += 1;

}

return paramString;

}Since, we have the base64 encoded encrypted password, we can write a small script that decrypts the password by first base64 decoding it and running it through a decryption algorithm corresponding to the above alogrithm, i.e. first XORing the bytes with 0x42 and then swapping the nibbles. The python script below does just that.

#!/usr/bin/python

import sys;

import base64;

b64pass = sys.argv[1];

encpass = base64.b64decode(b64pass);

encbytes = bytearray(encpass);

decstr = "";

for i in range(len(encbytes)):

x = encbytes[i];

x = x ^ 0x42;

x = ((x << 4) & 0xff) | ((x >> 4));

decstr += unichr(x);

print decstr;Run the above script with the base64 encoded encrypted password, and you have the correct password.

$ python decrypt.py BFF1NwF1YRTl

d1sW4s2ezIntermediate

The intermediate level tries to conceal its runtime behaviour by using reflection to call methods. Class names and method names are mildly encrypted.

Method localMethod1 = Class.forName(a("GjRA4PCM+3vihlyZPKtpdlX0ipqu26LbtXR9eIMXQHCm1lFllUrmmPH4", -7127332291234864623L)).getMethod(a("5RjJpGUtRnxRElI=", 1205579818242233630L), new Class[] { Integer.class });Here is the code used for decryption, before calling methods using reflection.

private static String a(String paramString, long paramLong)

{

Random localRandom = new Random(paramLong);

int i = 32 + localRandom.nextInt(128);

byte[] arrayOfByte1 = Base64.decode(paramString, 2);

byte[] arrayOfByte2 = new byte[arrayOfByte1.length];

byte[] arrayOfByte3 = new byte[16 + localRandom.nextInt(i)];

localRandom.nextBytes(arrayOfByte3);

for (int j = 0; j < i; j++)

{

int k = j % arrayOfByte1.length;

arrayOfByte2[k] = ((byte)(arrayOfByte1[k] ^ arrayOfByte3[(j % arrayOfByte3.length)]));

}

return new String(arrayOfByte2);

}To decrypt the class names and method names, we can study the above method. However, an easier alternative is to tamper the above method to make it print the decrypted class and method names before it returns them. To do this, we edit the smali code for the Verifier class and insert code to log the decrypted names.

:cond_0

new-instance v0, Ljava/lang/String;

invoke-direct {v0, v3}, Ljava/lang/String;-><init>([B)V

# Log the decrypted names

invoke-static {v0, v0}, Landroid/util/Log;->i(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;)I

return-object v0

.end methodRebuild and install the modified APK, and watch logcat when as we enter a password.

D/dalvikvm( 2533): No JNI_OnLoad found in /data/app-lib/org.teamsik.apps.hackingchallenge.intermediate-1/libpassword.so 0xa54138d8, skipping init

I/1337 ( 2533): 1337

I/org.teamsik.apps.hackingchallenge.Verifier( 2533): org.teamsik.apps.hackingchallenge.Verifier

I/getPassword( 2533): getPassword

I/java.lang.String( 2533): java.lang.String

I/isEmpty ( 2533): isEmpty

I/equals ( 2533): equals

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 374): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)With the help of above info, the decompiled code becomes a little more easier to understand. The app retrieves the password from the JNI library libpassword.so which exports a method Java_org_teamsik_apps_hackingchallenge_Verifier_getPassword, and then compares it with password submitted by the user. We can try to reverse engineer the above JNI method, but there is an easier alternative available. We can tamper with the code that retrieves the password and make it log it. Here is the method that does this.

public static boolean a(Context paramContext, String paramString)

{

try

{

int i = Integer.valueOf(a(b)).intValue();

Method localMethod1 = Class.forName(a("GjRA4PCM+3vihlyZPKtpdlX0ipqu26LbtXR9eIMXQHCm1lFllUrmmPH4", -7127332291234864623L)).getMethod(a("5RjJpGUtRnxRElI=", 1205579818242233630L), new Class[] { Integer.class });

Object[] arrayOfObject = new Object[1];

arrayOfObject[0] = Integer.valueOf(i);

Object localObject = localMethod1.invoke(null, arrayOfObject);

Class localClass = Class.forName(a("QryWaaVs/uvZcnetf5RA/g==", -2974850194083802263L));

Method localMethod2 = localClass.getMethod(a("4KJMndApHw==", -985673840903447778L), new Class[0]);

Method localMethod3 = localClass.getMethod(a("Ip+J+97c", 809623611412611158L), new Class[] { Object.class });

if (((Boolean)localMethod2.invoke(localObject, new Object[0])).booleanValue())

return false;

boolean bool = ((Boolean)localMethod3.invoke(localObject, new Object[] { paramString })).booleanValue();

return bool;

}

catch (Exception localException)

{

Log.e(a, "Error", localException);

}

return false;

}In the above code, password is retrieved from the JNI library by the call Object localObject = localMethod1.invoke(null, arrayOfObject);. We will edit the corresponding smali code to make it log the localObject after it makes this call.

invoke-virtual {v2, v3, v4}, Ljava/lang/reflect/Method;->invoke(Ljava/lang/Object;[Ljava/lang/Object;)Ljava/lang/Object;

move-result-object v2

# Log the result

check-cast v2, Ljava/lang/String;

invoke-static {v2, v2}, Landroid/util/Log;->i(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;)I

const-string v0, "QryWaaVs/uvZcnetf5RA/g=="Rebuild and install the modified APK, and watch logcat as we enter a password to see the dumped password.

D/dalvikvm( 3609): No JNI_OnLoad found in /data/app-lib/org.teamsik.apps.hackingchallenge.intermediate-1/libpassword.so 0xa5416f28, skipping init

I/1337 ( 3609): 1337

I/org.teamsik.apps.hackingchallenge.Verifier( 3609): org.teamsik.apps.hackingchallenge.Verifier

I/getPassword( 3609): getPassword

I/n0tQu1t3MyT3mp0( 3609): n0tQu1t3MyT3mp0

I/java.lang.String( 3609): java.lang.String

I/isEmpty ( 3609): isEmpty

I/equals ( 3609): equalsHard

The final challenge takes a number of measures to ensure that the password is never decrypted, and to conceal the runtime behaviour of the app. The password is secured using AES. Most of the method calls are made using reflection, to conceal the behavior of the app. The class names and method names are decrypted at runtime and then called, similar to the way it was done in the intermediate level. The hard level goes a step further by verifying if the app has been tampered with. This makes it difficult to run the modified version of the app, as we did in the previous level. Therefore, the analysis must be done is phases.

In the first phase, we must gain a better insight of the runtime behavior of the app. The class and method names are encrypted using AES, and are decrypted by the following method of d class.

private static String a(String paramString, long paramLong)

{

Random localRandom = new Random(paramLong);

paramString = Base64.decode(paramString, 2);

Object localObject = new byte['��'];

localRandom.nextBytes((byte[])localObject);

int i = localRandom.nextInt(1024);

localObject = new PBEKeySpec(Base64.encodeToString(new byte[localRandom.nextInt(32) + 16], 2).toCharArray(), (byte[])localObject, i + 512, 128);

localObject = new SecretKeySpec(SecretKeyFactory.getInstance("PBKDF2WithHmacSHA1").generateSecret((KeySpec)localObject).getEncoded(), "AES");

Cipher localCipher = Cipher.getInstance("AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding");

byte[] arrayOfByte = new byte[localCipher.getBlockSize()];

localRandom.nextBytes(arrayOfByte);

localCipher.init(2, (Key)localObject, new IvParameterSpec(arrayOfByte));

return new String(localCipher.doFinal(paramString));

}One way to retreive the decrypted class and method names is by tampering the above method, just like we did in the intermediate level. We tamper it to make it log the decrypted values just before it returns them to the caller method. To do this, we decomple the APK using apktool, and modify the smali code of the above method to inject logging code.

invoke-virtual {v2, v1}, Ljavax/crypto/Cipher;->doFinal([B)[B

move-result-object v0

new-instance v1, Ljava/lang/String;

invoke-direct {v1, v0}, Ljava/lang/String;-><init>([B)V

# log decrypted values

const-string v2, "d.a() returning: "

invoke-static {v2, v1}, Landroid/util/Log;->i(Ljava/lang/String;Ljava/lang/String;)I

return-object v1

.end methodThis tampering would be detected by the app, but it should still log the decrypted class and method names when we enter a password.

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 397): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 397): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)

D/dalvikvm( 397): GC_CONCURRENT freed 1771K, 26% free 8164K/10984K, paused 0ms+0ms, total 7ms

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): java.security.cert.CertificateFactory

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): java.security.cert.Certificate

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): java.security.PublicKey

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): java.io.ByteArrayOutputStream

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): android.util.Base64

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): java.lang.String

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): getInstance

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): generateCertificate

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): getPublicKey

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): getEncoded

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): getEncoded

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): toByteArray

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): encodeToString

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): equals

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): NO_WRAP

I/d.a() returning: ( 1684): X.509

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 397): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)

D/MobileDataStateTracker( 397): default: setPolicyDataEnable(enabled=true)The knowledge gained from the above log, when combined with the decompiled code in JD-GUI, makes it somewhat easier to figure out the runtime behaviour of the app. The app retrieves the public key of the signing certificate at runtime, and uses it as one of the parameters to the encryption algorithm that is used to encrypt the user input using AES. This encrypted value is then compared with a encrypted value hardcoded in the app in base64 encoded form. The encryption used here is a password based encryption, where password is derived from the public key of the signing certificate. The salt and the IV used in the AES encryption are also hardcoded in the app in base64 encoded form. The snippet below shows the code responsible for performing the encryption on the user input.

paramContext = "rym6wS4ddfaGkTuLfwfDFA==:3I2sjvOYVSQRoclg3BNfCQ==:Lg/ocYTs564fO2W3Luh3QUQmMmDVkhLjsKzGPSZT2ws=".split(":");

if (paramContext.length != 3) {

return false;

}

localObject2 = Base64.decode(paramContext[0], 2);

Object localObject4 = Base64.decode(paramContext[1], 2);

localObject3 = new PBEKeySpec(((String)localObject3).toCharArray(), (byte[])localObject4, 8192, 128);

localObject3 = new SecretKeySpec(SecretKeyFactory.getInstance("PBKDF2WithHmacSHA1").generateSecret((KeySpec)localObject3).getEncoded(), "AES");

localObject4 = Cipher.getInstance("AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding");

((Cipher)localObject4).init(1, (Key)localObject3, new IvParameterSpec((byte[])localObject2));

paramString = ((Cipher)localObject4).doFinal(paramString.getBytes());

arrayOfObject[6] = arrayOfMethod[6].invoke(null, new Object[] { paramString, Integer.valueOf(new Field[] { localObject1 }[0].getInt(null)) });

boolean bool = ((Boolean)arrayOfMethod[7].invoke(arrayOfObject[6], new Object[] { paramContext[2] })).booleanValue();

return bool;As tampering with the app would change the signing certificate and the public key, and hence the password for the AES encryption, we must use a runtime attack on the unmodified app to retrieve the password. The app does not use any anti-debugging techniques, which makes it easier to attach a debugger at runtime. So let’s install the original APK and run it. We must enter a password once to make sure all the relevant classes are loaded. Once the app is running and the password is entered, we can attach jdb to the running app.

$ adb shell ps | grep teamsik

u0_a53 1789 160 534616 71884 ffffffff b75bf9eb S org.teamsik.apps.hackingchallenge.hard

$ adb forward tcp:12345 jdwp:1789

$ jdb -attach localhost:12345

Set uncaught java.lang.Throwable

Set deferred uncaught java.lang.Throwable

Initializing jdb ...

> As seen in the above decompiled code, the password is used as the first argument to PBEKeySpec constructor. We can put a breakpoint on this constructor in order to dump the password.

>

Breakpoint hit: "thread=<1> main", java.security.MessageDigest.digest(), line=276 bci=0

<1> main[1] stop in javax.crypto.spec.PBEKeySpec.<init>(char[], byte[], int, int)

Set breakpoint javax.crypto.spec.PBEKeySpec.<init>(char[], byte[], int, int)

<1> main[1] cont

>

Breakpoint hit: "thread=<1> main", javax.crypto.spec.PBEKeySpec.<init>(), line=74 bci=1

<1> main[1] locals

Method arguments:

password = instance of char[28] (id=831731734904)

Local variables:

salt = instance of byte[16] (id=831731734840)

iterationCount = 8192

keyLength = 128

<1> main[1] dump password

password = {

p, X, K, M, g, /, 7, c, y, f, y, Y, O, E, v, 1, Z, 6, W, J, e, t, s, p, g, y, M, =

}Now that we have the AES encryption password, we can write a small decryption code that decrypts the hardcoded encrypted password for the app, using this dumped encryption password and the hardcoded salt and IV. Since I feel lazy after all the above hard work, I am just gonna rip off the decompiled code from JD-GUI to do this, with some modifications of course.

import java.util.Base64;

import java.io.ByteArrayInputStream;

import java.io.InputStream;

import java.lang.reflect.Field;

import java.lang.reflect.Method;

import java.security.Key;

import java.security.MessageDigest;

import java.security.spec.KeySpec;

import java.util.Random;

import javax.crypto.Cipher;

import javax.crypto.SecretKey;

import javax.crypto.SecretKeyFactory;

import javax.crypto.spec.IvParameterSpec;

import javax.crypto.spec.PBEKeySpec;

import javax.crypto.spec.SecretKeySpec;

public class decrypt {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String paramContext[] = { "rym6wS4ddfaGkTuLfwfDFA==", "3I2sjvOYVSQRoclg3BNfCQ==", "Lg/ocYTs564fO2W3Luh3QUQmMmDVkhLjsKzGPSZT2ws=" };

Object localObject3 = "pXKMg/7cyfyYOEv1Z6WJetspgyM=";

Object localObject2 = Base64.getDecoder().decode(paramContext[0]);

Object localObject4 = Base64.getDecoder().decode(paramContext[1]);

byte[] ct = Base64.getDecoder().decode(paramContext[2]);

localObject3 = new PBEKeySpec(((String)localObject3).toCharArray(), (byte[])localObject4, 8192, 128);

try {

localObject3 = new SecretKeySpec(SecretKeyFactory.getInstance("PBKDF2WithHmacSHA1").generateSecret((KeySpec)localObject3).getEncoded(), "AES");

localObject4 = Cipher.getInstance("AES/CBC/PKCS5Padding");

((Cipher)localObject4).init(2, (Key)localObject3, new IvParameterSpec((byte[])localObject2));

byte[] paramString = ((Cipher)localObject4).doFinal(ct);

System.out.println(new String(paramString));

} catch(Exception e) {

System.out.println(e.toString());

}

}

}Let’s compile and run the above code, and if all is well, it should print out the decrypted password.

$ javac decrypt.java

$ java decrypt

t34mS1K$4lut35Y0u!